The Treasury Department is considering issuing an ultra-long bond with a maturity greater than 30 years. The idea was first raised in post-election interviews with then-nominee for Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and formalized last month when Treasury requested a response on the subject from primary dealers and the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC). Both of these groups advised Treasury against issuing an ultra-long bond, primarily on the grounds that demand for the product would be insufficient to support substantial issuance on a sustained basis. TBAC specifically argued that “pension plans would not be a large or reliable source of demand for ultra-long issuance.”

From NISA’s perspective, that assessment underestimates the potential demand from pensions for a longer maturity Treasury offering. We know from experience the challenge plan sponsors face in hedging their liabilities beyond 30 years, and believe that pensions would benefit from the added flexibility a 50-year bond would offer. (For reference, assuming a 3% yield, the duration difference between the 30-year bond and a 50-year bond would be about six years.) And the United States would not be an outlier in issuing a bond of this maturity. Other countries, including the UK and Italy, have recently issued 50-year bonds, and a few have even begun issuing 100-year securities.

To estimate pension demand for a 50-year Treasury bond, we applied the liability cashflow profile of the PBO-weighted aggregation of NISA’s corporate DB clients to the entire $3.6 trillion in liabilities of the corporate DB pension community. Based on this analysis and our expectations for funded status and hedge ratios, we estimate that corporate DB pension plans would purchase $200-250 billion in 50-year Treasuries over the next decade. Importantly, our estimates do not include the insurance industry, DC plans, public pensions, or any other segment of the retirement market, which could substantially increase demand for these securities independent of corporate DB plans.

We have shared our thinking with Treasury’s Office of Debt Management. Based on our analysis, we advised Treasury that we believe there would be strong demand for $20-30 billion of a 50-year bond per year for the next decade at a yield not much higher than that of the 30-year bond. We recognize that demand estimation is only one element of Treasury’s decision-making process, and acknowledge that any new product offering must clear a high hurdle in the form of the “regular and predictable” mantra that has come to characterize Treasury’s debt management policy over the last four decades. That policy eschews opportunistic or tactical issuance based on the current level of interest rates, and would only recommend issuing an ultra-long bond if confidence was very high that the product would succeed as a permanent addition to Treasury’s financing mix. To that point, the possibility of an ultra-long bond has been officially discussed by Treasury—and subsequently dismissed—on at least four separate occasions since 2006.

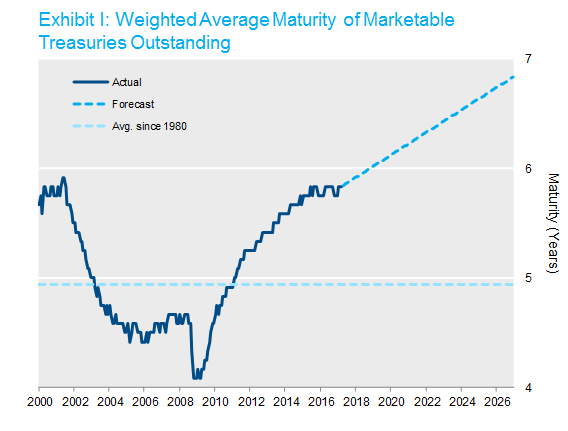

Treasury’s most recent public statement on the topic says only that they are “currently studying the possibility.” The decision ultimately lies with the treasury secretary (and by extension the president), who has the option to proceed against the advice of TBAC, the dealers, and even his own staff should he so choose. If the secretary’s motivation is to extend maturity at a time of low interest rates, he doesn’t need to issue an ultra-long bond. As shown in the chart below, Treasury has already extended their weighted average maturity to near historical highs in the last few years, and the current issuance pattern will continue this trend for years to come.

Source: U.S. Treasury. The forecast assumes constant issuance sizes and patterns.

Any ultra-long bond issue would be so small relative to the aggregate Treasury debt outstanding that it wouldn’t significantly change the trajectory of the forecast line above. The secretary is surely aware of this dynamic, as he continues to discuss ultra-long bonds publicly since taking office. It could be the case that his motivation is not just the fundamental logic of extending maturity, but also includes the value of headline-grabbing innovations of the government’s funding strategy.

If Treasury does decide to bring an ultra-long bond to market, we would expect the first auction to occur sometime in 2018, based on the history of new Treasury products. We’ll be keeping an eye on the quarterly refunding statements in August and November for any update on Treasury’s thinking, and will continue to advocate for the idea in the meantime.