The Federal Reserve took the first step this week of what will be a long journey towards normalizing its balance sheet after buying nearly $4 trillion in securities from 2008 through 2014. The Fed had $8.7 billion in Treasury securities that matured on October 31. When those bonds matured, $2.7 billion was reinvested back into the five Treasury coupon securities issued on the same day while the remaining $6 billion was allowed to mature without reinvestment, and the Fed’s balance sheet shrank by that amount. The Fed also reduced its holdings of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) holdings by $4 billion in October, though that process is slightly different and takes place in various steps throughout the month. The combined $10 billion reduction represents the first small step in a process that will see the Fed’s balance sheet shrink by as much as $2 trillion over the next three to five years. Interestingly, the journey begins with imperfect knowledge of the final destination, since the Fed does not currently know the appropriate normalized size of its balance sheet.

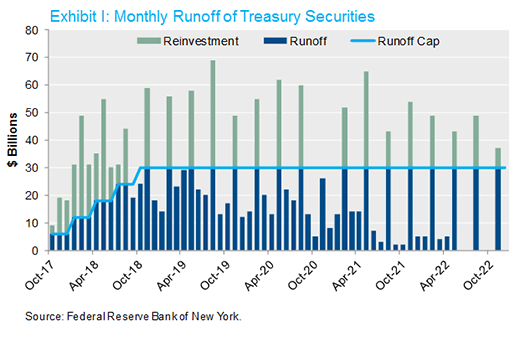

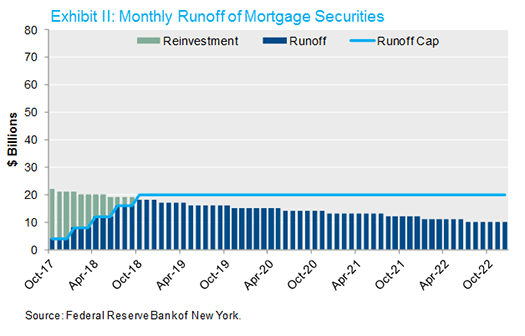

The Fed has chosen to normalize its balance sheet exclusively through allowing securities to mature without reinvestment. Currently, the Fed does not anticipate selling any assets, with the exception of some residual holdings of MBS at the end of the process. The Fed has chosen to ease gradually into the process by limiting the amount of Treasuries and MBS that will run off in each month. The caps start small at $6 billion per month for Treasuries and $4 billion for MBS, but increase steadily over the next year to terminal caps of $30 billion and $20 billion, respectively. Monthly maturities in excess of the caps will be reinvested. The charts in Exhibit I and Exhibit II below show the timeline of the runoff and reinvestment of Treasuries and mortgage securities, respectively for the next five years. Mortgages are projected to mature at a significantly slower pace than Treasuries, but prepayment speeds are of course unknown and dependent on the level of interest rates, among other factors.

The Fed believes this passive runoff process will be less disruptive to markets than asset sales, which fits with their stated desire to push balance sheet policy to the background and focus on the overnight interest rate as their primary tool. That said, quantitative easing from 2008 to 2014 is thought to have had dramatic effects, and the Fed has now become the first central bank to begin unwinding its crisis-era balance sheet expansion. Because of the novelty of this action and the unknown terminal size of the balance sheet (thought to be approximately $2.5 – $3.5 trillion around 2022), considerable uncertainty exists as to the impact on the yield curve and mortgage spreads. We’ll be keeping a close eye on the normalization process and any potential market impact, but we wanted to highlight that the gears have now officially been set in motion.