COVID-19 has delivered an economic shock of unprecedented speed and severity. The Federal Reserve under Chairman Powell has responded with the most aggressive policy action in the central bank’s 107-year history. As well as cutting the policy rate to essentially zero and offering nearly unlimited repo financing, the Fed commenced on March 13, an asset purchase program of staggering proportions. In the ensuing 13 trading days, the Fed purchased $837 billion of Treasuries, more than it bought in the entire 20 months of QE3. These purchases helped to reverse a disconcerting deterioration of liquidity in the Treasury market and contributed to a $2.5 trillion increase in the Fed’s balance sheet. The Fed continued by announcing a series of emergency lending facilities to thaw frozen credit markets. These included a renewal of 2008 facilities targeting money funds, commercial paper, and asset-backed securities as well as novel forays into the corporate and municipal bond markets.

Of these, only the commercial paper and money fund facilities are fully operational as of May 19 (the corporate bond facility purchased $305 million in ETFs last week, but has yet to purchase any bonds). The implementation details of the emergency lending programs could have important relative value implications, and we’ll be following them carefully in the coming months. In this note, however, we want to focus on the immediate impacts of the Fed’s actions, which were to reverse the sharp deterioration in risk sentiment, instill confidence, and reduce volatility across a range of asset classes. A comment by Chairman Powell at the April FOMC press conference demonstrates that he well understands this announcement effect:

“When we announce these facilities… it’s not just the actual lending we do, we build confidence in the market. And private market participants come in and many companies that would’ve had to come to the Fed have now been able to finance themselves privately since we announced the initial term sheet on these facilities. So, that’s a good thing. Companies are out there financing; they’re out there raising liquidity. We haven’t made any corporate loans in those facilities—we’ve made the short-term money-market loans—but we haven’t made many of them. And yet, there’s a tremendous amount of financing going on, and that’s a good thing. So, we, for that reason, the ultimate demand for the facilities is quite difficult to predict because there is this announcement effect that really gets the market functioning again. Of course, we have to follow through. And we will follow through to validate that announcement effect.”

FOMC Chairman Jerome Powell, April 29, 2020.

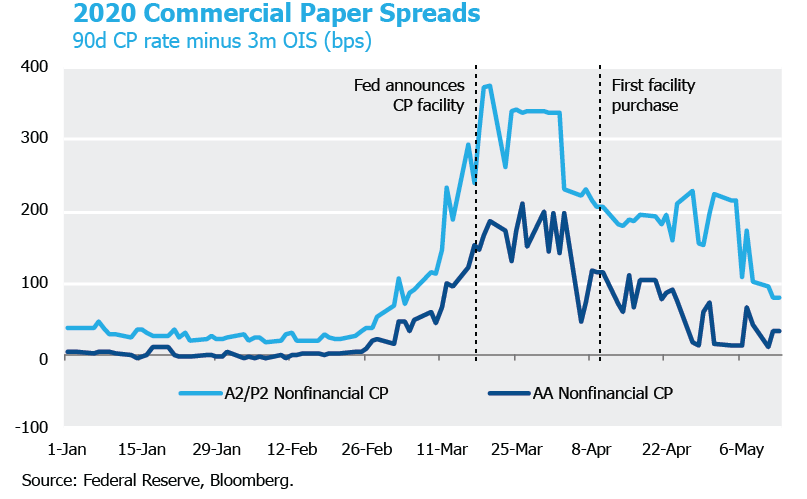

Those are strong words from a man with an unlimited balance sheet at his disposal. And the Fed’s words have had powerful effects. Everyone can feel the change in sentiment and see the reversal of equity prices, but we can also pinpoint the turnaround in specific markets to the day the Fed announced its interventions. Confidence was restored; credit spreads tightened; and outflows switched to inflows. For example, the Fed announced its commercial paper facility on March 17 following a dramatic widening in spreads and sudden stop in new issuances. The facility didn’t report its first purchase until April 9, by which time spreads had retraced most of the widening. As of the latest report on May 14, the facility had only purchased $4 billion worth of securities, a tiny fraction of the $1.1 trillion commercial paper market. Yet spreads have mostly normalized as the Fed’s announcement gave private investors the ‘all clear’ signal to resume investing in the asset class.

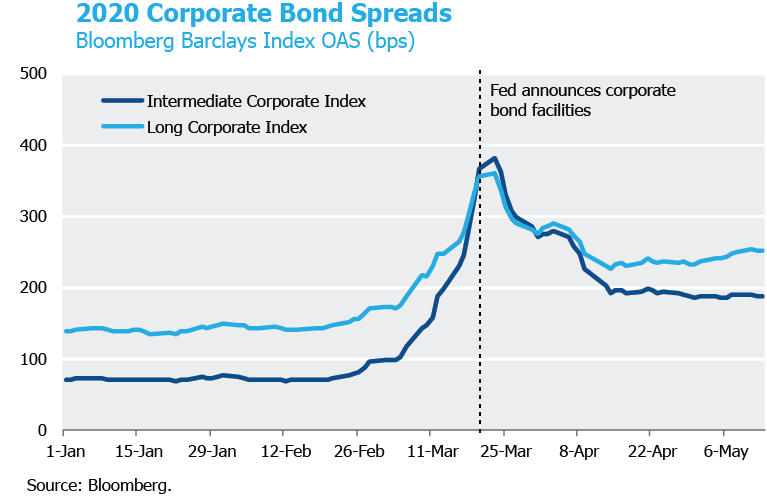

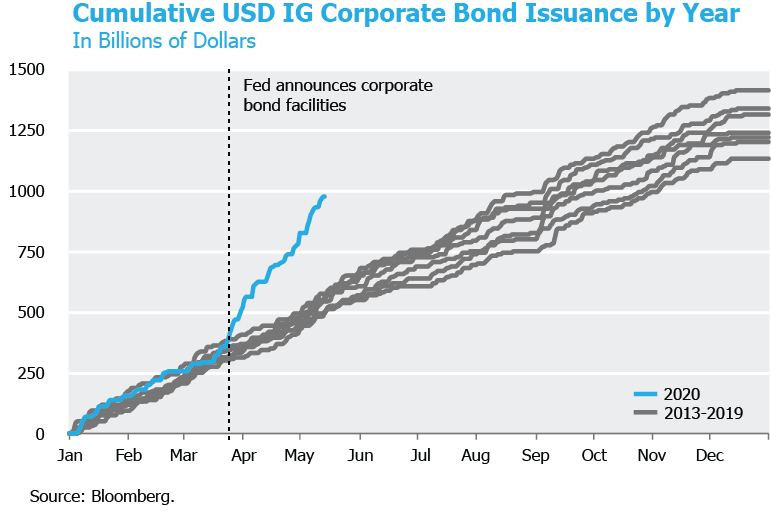

Nowhere is the Fed’s ability to reopen markets with words more apparent than in the corporate bond market. The FOMC announced its first-ever intervention into corporate bonds on March 23. Though the Fed has yet to purchase a single bond, the announcement date precisely marked the reversal in corporate bond spreads. Spreads tightened across the entire curve despite the Fed’s facility limiting purchases to bonds with maturities of 4 years or less. Even more remarkably, spreads tightened despite a record surge of issuance. Without buying a single bond, the Fed helped create the conditions that allowed corporate America to raise over $600 billion in long-term financing to weather the pandemic. As Powell noted, some of those companies may have required Fed assistance had they been unable to raise private capital.

The announcement effect is a potent force when you carry an unlimited balance sheet and the credibility to follow through on your commitments. Communication is as important as implementation when a central bank is performing the lender of last resort function during a crisis. Powell has learned the lessons from past crisis firefighters like Hank Paulson, who famously said in 2008, “If you have a bazooka in your pocket and people know it, you may not have to take it out.”

By swiftly committing to a policy response of overwhelming force, the Fed may have limited the number of dollars it will ultimately have to add to its balance sheet. Participation in the emergency lending facilities could be surprisingly small six months from now. There will come a time to consider the potential for negative consequences resulting from the Fed’s aggressive actions. For now, we’re glad that Chairman Powell has wielded his communication tools effectively to reduce the downside risks to the U.S. economy posed by the COVID-19 crisis.

To download a PDF version, please click here.