Like so many K-12 teachers having to remind their students about the lessons they forgot over the summer, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell’s speech in Jackson Hole last week was in many ways a recitation of the message he and his colleagues have delivered all year. There is no denying that Fed communications have gathered an increasing urgency throughout the year as inflation has accelerated. We commend Chairman Powell for the clarity and forcefulness with which he delivered his remarks, but it is a fact that nearly every element of Chairman Powell’s message had been delivered previously.

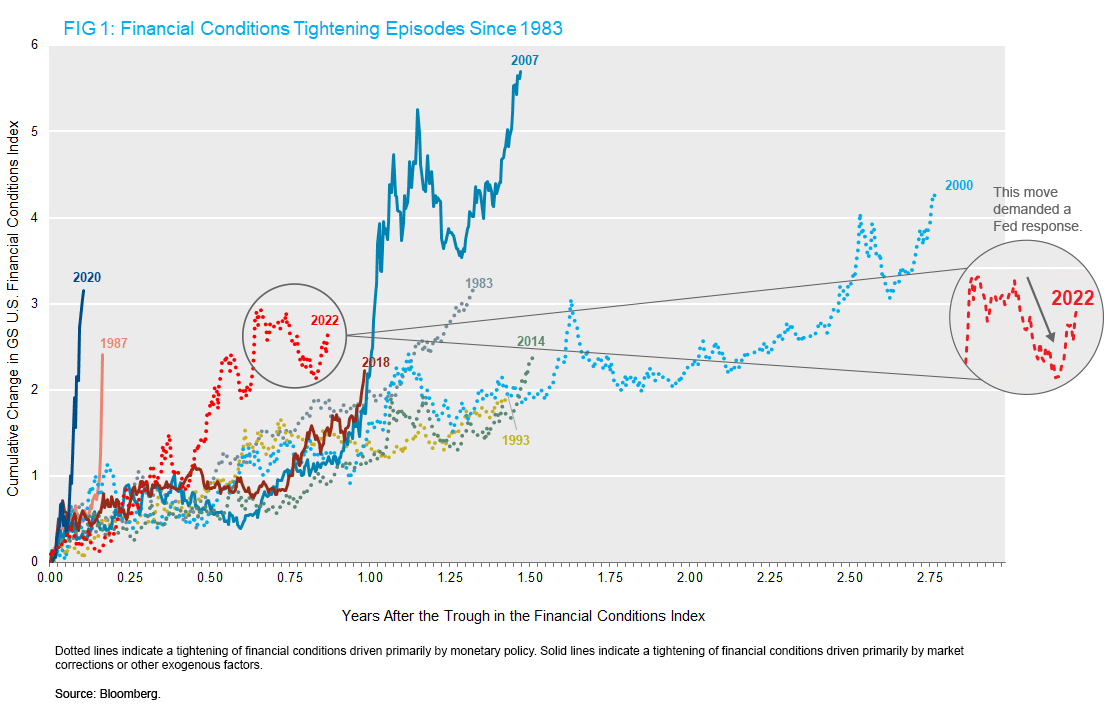

The other factor driving Powell to convey such resolve was the incongruous easing of financial conditions that had arisen since late June. Policymakers use the term “financial conditions” to describe the broad constellation of asset prices and other variables that influence economic behavior. There are many indices of financial conditions. In this note, we refer to the Goldman Sachs index, which is a weighted average of the federal funds rate, the 10-year Treasury yield, corporate bond spreads, equity prices and the exchange rate. Over the last several decades, the Fed has increasingly focused on financial conditions as a primary transmission channel through which monetary policy impacts the economy.

Powell himself told us as early as January that a tightening of financial conditions would be appropriate given the circumstances. With the benefit of hindsight, we suspect many investors wish they had taken him at his word. On the rare occasion when a Fed Chairman explicitly calls for tighter financial conditions, he tends to get them. Powell has attained tighter financial conditions this year, with rapid increases in interest rates, record declines in fixed income and equity indices, and a substantial appreciation of the dollar. As we show in Figure 1, the tightening of financial conditions in 2022 represents the fastest policy-induced tightening on record. The two episodes in which conditions tightened faster were catalyzed by exogenous shocks (the pandemic in 2020, and the Black Monday stock market crash in 1987).

That tightening was hard-won by the Fed with a lot of tough talk backed up by historic actions: 225 basis points of rate hikes in four meetings, the fastest pace of rate hikes since Chairman Paul Volcker’s tenure in the early 1980s. With inflation being the primary factor driving the Fed’s aggressive behavior, market participants have been eager to call the top in inflation and start looking ahead to the end of the Fed’s rate-hiking cycle. This narrative began to take hold in late June, leading to a significant easing of financial conditions, as can be seen in the highlighted section of the chart. This easing undid some of the Fed’s hard work and conflicted with their goal of restraining economic growth and reducing inflation.

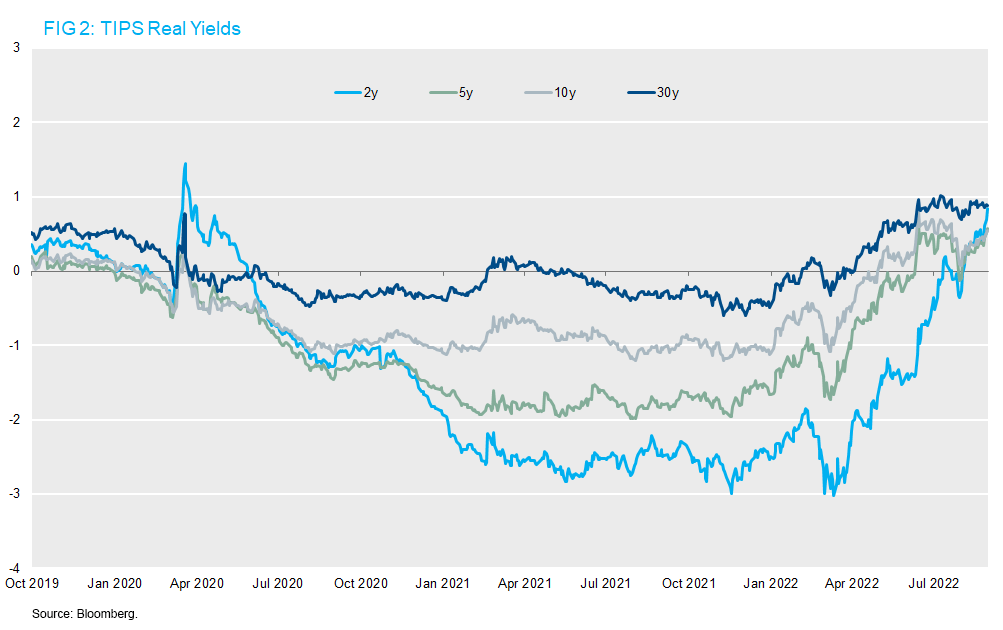

A series of Fed speakers took to the airwaves in the first week of August to push back against the perception of an impending dovish pivot by the Fed. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly and Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said that the Fed’s work was “far from done,” and that it would be premature to declare victory against inflation. Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari spoke directly to bond traders when he said that the 2023 rate cuts then priced into markets “seem like a very unlikely scenario.” Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin took it one step further on August 12 by citing precise levels of individual asset prices, a potentially dangerous game the Fed tries to avoid playing. Specifically, he said that he wants to see positive real yields at all maturities across the yield curve. This comment was notable because the Fed had only achieved this feat on July 11 when 2-year TIPS yields finally turned positive, as shown in Figure 2.

This success was fleeting, as 2-year real yields quickly fell back below zero and equity prices kept rising through mid-August despite this coordinated communications effort from the Regional Fed Presidents. Thus, it became necessary for Chairman Powell to drop the hammer last week, leaving no doubt about the Fed’s resolve to do whatever is necessary to bring inflation down and prevent a catastrophic de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

Market participants seem to have gotten the message this time. Not only has the S&P 500 declined by 5% since Powell’s speech, but the 2-year real yield has risen by 35 basis points to a cycle high of +84 basis points. Perhaps they needed to hear it from Jay “Plain English” Powell, whose communication style is better suited to a high school economics course rather than a graduate seminar (that’s a compliment if you couldn’t tell). Recall that Powell is the first Federal Reserve Chairman without an economics Ph.D. since Paul Volcker. Maybe that lack of credential is an attribute rather than a shortcoming?

As we’ve been saying since the springtime, 8-9% inflation means that the “Fed put” is farther out of the money than it has been at any point since most of today’s investors joined the workforce. The Fed deserves plenty of criticism, for allowing real yields to remain far too low for far too long in 2021, and more generally for conditioning generations of investors to believe in the “Fed put.” But once they realized their mistake late last year, they have been steadfast in correcting it. That adjustment means higher yields and tighter financial conditions, as Powell has been telling us since January. Some market participants didn’t want to listen. As children across the nation return to the classroom, another generation of traders has been schooled in the folly of fighting the Fed.