The May jobs report produced the biggest surprise we have ever seen from an economic data release. Nonfarm payroll employment increased by 2.5 million in the month, a full 10 million jobs higher than the Bloomberg median forecast for a loss of 7.5 million jobs. Not a single one of the 78 economists surveyed by Bloomberg predicted a positive number. There are currently 21 million unemployed persons, so economists missed their forecast by almost half the total stock of unemployment.

We are not here to pick on forecasters (though that can be fun at times). We write today to welcome the news that the labor market appears to have reached bottom earlier than anyone expected. The reference period for the jobs report is the week that includes the 12th day of the month, so these jobs were created by early May when the reopening was still in its early stages. This timing is consistent with real-time credit card spending and other high frequency data that suggest the trough in economic activity occurred around the third week of April. If this bottom holds, the 2020 recession will be the most severe since WWII but also the shortest in American history, lasting only two or three months from peak to trough.

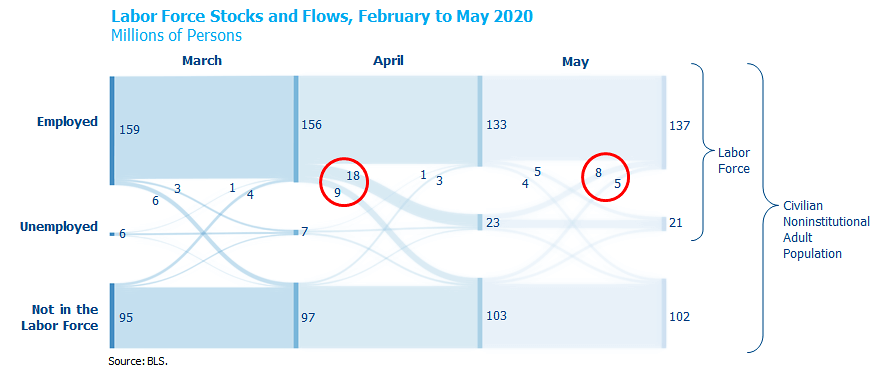

The underlying details of the jobs report are even stronger than the headline figure. The household survey (one of the two surveys that comprise the Employment Situation Report) monitors the flow of workers between employment, unemployment and nonparticipation in the labor force. Every American 16 years and older who is not in the military or in prison falls into one of these three categories. The number of employed workers declined by 26 million in March and April before rebounding by 4 million in May. Those are enormous swings, but they are net figures that mask even greater volatility in gross flows, as shown in the diagram below. 27 million workers were separated from employment in April, nearly four times higher than the previous record. 18 million of these flowed to unemployment. However, the 14.7% April unemployment rate (the ratio of unemployed workers to the total labor force) understated the degree of job loss because an additional 9 million workers left the labor force directly from employment.

Our optimistic read on these flow data stem from the fact that the pace of separations is falling while the pace of hirings is rising. While total separations decreased from 27 million in April to 9 million in May, total hires increased from 4 million to 13 million. The fact that businesses had already re-hired 13 million employees in just the first few weeks of reopening through early May bodes well for a rapid recovery in employment. Many of these rehirings were likely supported by funding from the Paycheck Protection Program, one of the small business provisions in the fiscal stimulus package. We expect these trends to continue as the reopening proceeds, which should lead to a higher pace of net job growth in the coming months.

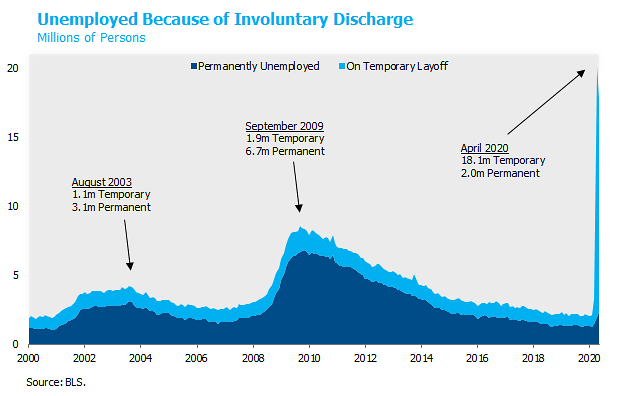

The composition of the stock of unemployed workers also supports our optimistic view. Of the 20 million workers unemployed because of involuntarily discharge in April, fully 90% classified themselves as temporarily unemployed. These could be, for example, servers whose restaurants have closed but who expect to return to work upon reopening. This classification is a self-assessment from household survey respondents, so there is some risk that their jobs do not return and they shift to permanently unemployed. For now, only 2 million considered themselves permanently unemployed, which is well below the level of 2008 and below even the level of the mild 2001 recession. The sooner-than-expected rebound in hiring gives us hope that the vast majority of unemployment in this recession will indeed be temporary.

As we’ve said before, we believe the economy will recover from this self-induced coma much more quickly than it would from a traditional business cycle recession. The May jobs report suggests that the initial recovery in the labor market could be V-shaped. It remains to be seen whether the broader economic recovery will extend sufficiently to regain nearly all of the February peak in activity in a short period of time, or whether it will plateau at some lower level. The risk of a second wave of the virus remains. But the risk that a prolonged shutdown would plunge firms and households into financial distress has been attenuated somewhat by the earlier-than-expected rebound in activity (not to mention generous fiscal stimulus). The recovery has a long road ahead, but the first turn has been navigated with vigor.