The longest expansion in U.S. economic history ended in February. March ushered in a recession that will be unlike any other we have seen before. In the last five weeks, 26 million workers have filed for unemployment insurance. That’s more than the total number of jobs that were created in the entire decade-long expansion. The unemployment rate looks likely to surge from a 50-year low of 3.5% in February to 15 or 20% just two months later. This would be the highest unemployment rate since the Depression.

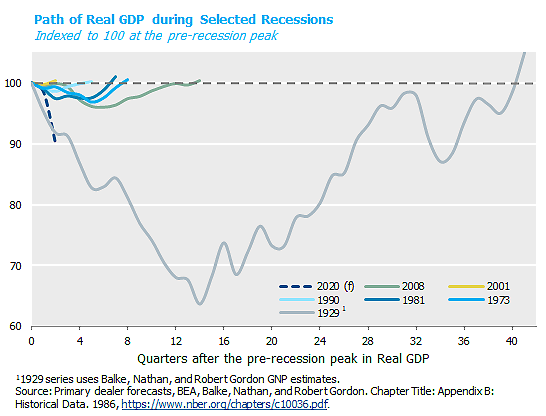

Never before has the economy experienced a sudden stop of such magnitude and global synchronization. In the average of the last five U.S. recessions dating back to 1973, real GDP contracted by 2.3% peak-to-trough, bottomed after four quarters and regained the pre-recession peak after seven quarters. In 2020, real GDP is expected to contract by 7-10% in the second quarter alone (approximately 28-40% annualized, though we don’t think it makes much sense to annualize the data in this context). The second quarter could very well be the worst quarter of economic growth in U.S. history, if it surpasses the 7% real GDP decline in the fourth quarter of 1933.

Ironically, the magnitude of the decline and the dizzying speed with which it has occurred make this recession less frightening to us from an economic perspective than it would be otherwise. This is not a normal business cycle recession. The economy did not overheat and cause a misallocation of resources that subsequently required purging. This is a voluntary economic shutdown in pursuit of a public health goal. If we can successfully address the public health crisis in a timely fashion (which remains far from certain at this point), it seems plausible that we will be able to reopen the economy and resume healthy growth.

That said, we do not expect a V-shaped recovery for the economy as a whole. Social distancing will only be relaxed gradually and with much geographic dispersion. Some individual cities or regions that have been relatively unaffected by the virus might exhibit V-shaped recoveries, but prudent sequencing of the reopening around the country will make the aggregate nationwide recovery appear more U-shaped. Even if we could somehow reopen the entire national economy all at once – say in the case of a miracle cure – an economic shock this severe is bound to have some lasting effects. You simply can’t put 26 million people out of work and shutter thousands of firms for two months without leaving scars. Policymakers are working hard to prevent otherwise sound businesses from falling into financial distress during the shutdown, but there are bound to be some bankruptcies. The aggressive fiscal response will take the federal deficit above 15% this year (its highest level since World War II), but a sharp decline in tax revenue is likely to put severe pressure on state and local budgets and cause some degree of fiscal tightening at the subnational level. Turmoil in the energy sector further complicates matters. These factors will slow the pace of the recovery, but rest assured: the fundamental health of the U.S. economy remains far stronger than the catastrophe that will be reflected in the Q2-2020 data.