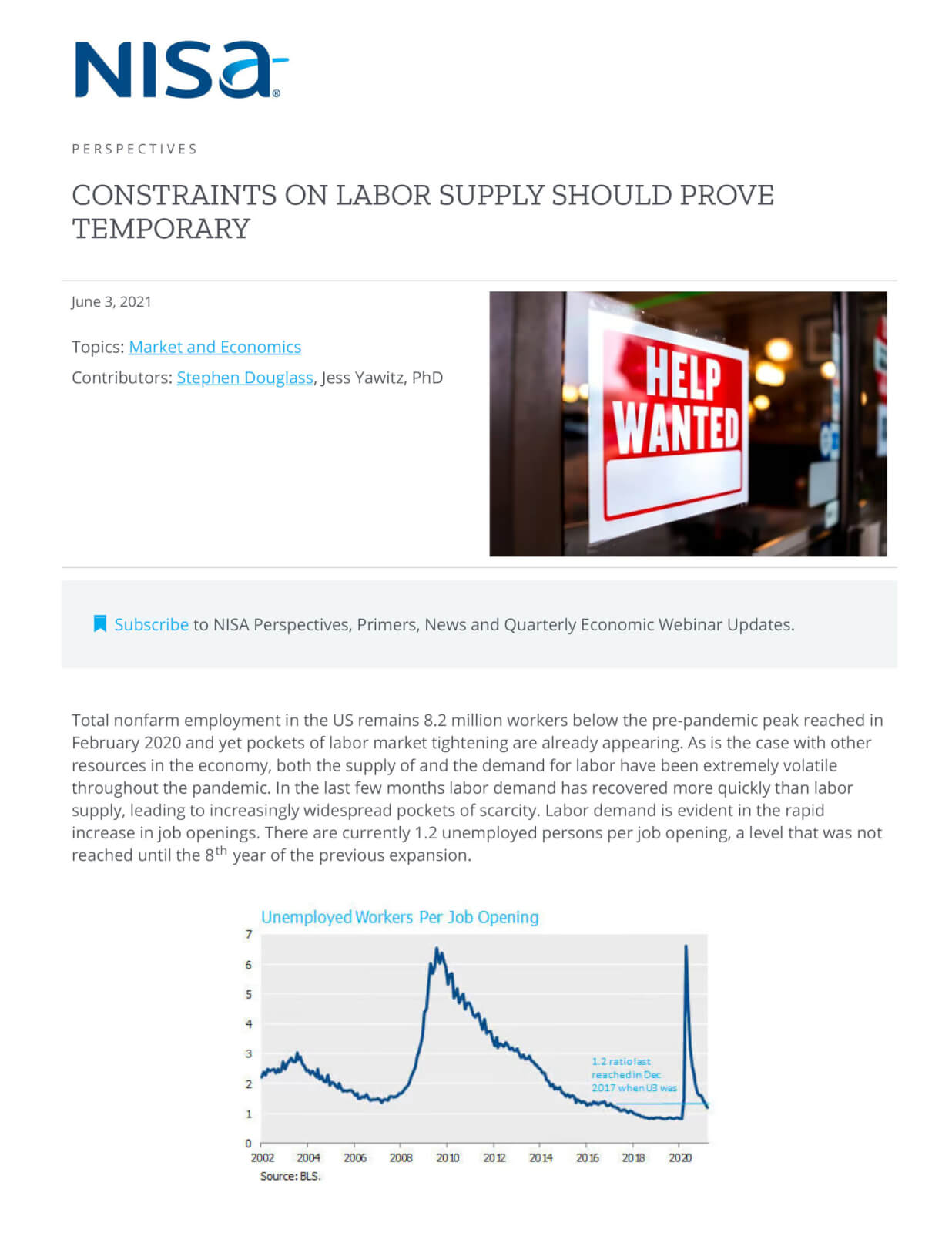

Total nonfarm employment in the US remains 8.2 million workers below the pre-pandemic peak reached in February 2020 and yet pockets of labor market tightening are already appearing. As is the case with other resources in the economy, both the supply of and the demand for labor have been extremely volatile throughout the pandemic. In the last few months labor demand has recovered more quickly than labor supply, leading to increasingly widespread pockets of scarcity. Labor demand is evident in the rapid increase in job openings. There are currently 1.2 unemployed persons per job opening, a level that was not reached until the 8th year of the previous expansion.

We believe generous unemployment benefits are disincentivizing work as has been widely reported, but this is only one factor constraining labor supply. Fear of COVID-19 (“COVID”) and lack of childcare are the other two having the largest impact, in our opinion. We believe the impact of all three factors will fade quickly over the next few months and allow for a clearer picture of the health of the labor market and the economy.

Work Disincentive from Unemployment Benefits

There are currently 16.3 million people earning one of the various forms of unemployment insurance benefits. Unemployment benefits replace more than 100% of prior income for about half of the 9.8 million workers currently unemployed. Leisure & hospitality and retail are the two lowest wage industries in the economy and therefore have the highest unemployment insurance benefit replacement rates, well above 100% in many cases. These two sectors remain well below pre-pandemic employment levels and exhibit elevated signs of tightness. The $300 per week federal supplement to regular state unemployment insurance expires September 6 for all workers. 25 states, all with Republican governors, have announced that they will terminate this benefit earlier than that.

Fear of COVID

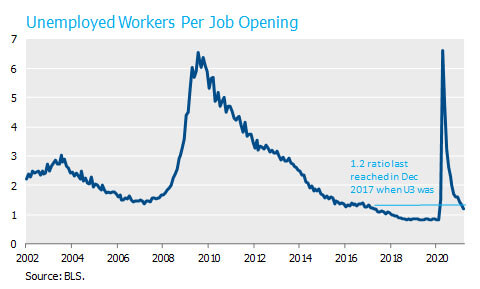

Despite the resounding success of the vaccination campaign, only 41% of the US population was fully vaccinated as of Memorial Day. Because vaccination began with the elderly (many of whom are retired), the share of the labor force that is fully vaccinated is probably below 30%. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has conducted a supplemental survey asking how many workers have left the labor force because of the pandemic. That figure has declined from 9.7 million in May 2020 but remained elevated at 2.8 million as of the last reading in April 2021. Now that vaccine supply is abundant, fear of the virus should be fading fast.

Lack of Childcare

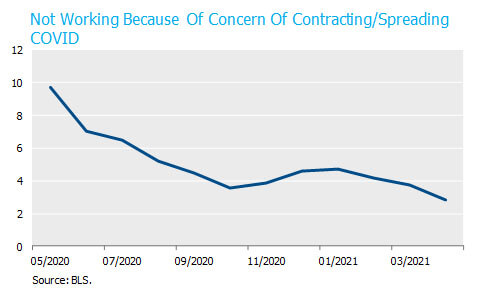

Millions of parents have experienced the disruption to their work life from young children remote learning during the pandemic. Only about half of the K-12 schools in the country have returned to in-person instruction. Employment has recovered more in states where schools have more fully reopened. Daycare centers are also only back to 58% of pre-pandemic attendance. A fascinating study from the San Francisco Fed demonstrated that mothers are shouldering most of the burden. Specifically, the labor force participation rate for mothers has lagged as fathers and childless adults have mostly returned to work, resulting in about 700,000 fewer women in the labor force according to the Fed’s estimate. Childcare availability will vary over the summer, but shouldn’t be a problem once the schools reopen fully in the fall.

Labor is the largest resource in the US economy. Demand for workers is surging as we expected during the reopening. That the supply of labor is being so disrupted (by self-inflicted policy errors in some cases) has come as a surprise and held back the pace of recovery. Though the half-life remains uncertain we believe these labor supply constraints will decay over time, and that a recovery in labor supply will allow for an increased pace of hiring as we move from summer into fall. We anticipate that the economy will recover a substantial portion of the remaining 8.2 million job shortfall this year and allow the Fed to begin the discussion of tapering the pace of asset purchases sometime between the September and December FOMC meetings.

Download the PDF

To download a PDF version, please click here.