Limited Direct Impact From The Downgrade

Fitch Ratings surprised market participants late Tuesday by downgrading the sovereign credit rating of the U.S. Government from AAA to AA+, citing “expected fiscal deterioration over the next three years, a high and growing general government debt burden, and the erosion of governance…over the last two decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.” Fitch left their country ceiling unchanged at AAA, which is important for corporate and municipal issuers. We find the timing of their announcement, and arguably the rating level itself, to be rather arbitrary. Fitch does not possess any proprietary information about the U.S. fiscal position, so their decision does not have any impact on our assessment of the safety of U.S. Treasuries. Consequently, we do not anticipate taking any portfolio action as a direct result of Fitch’s announcement.

The Fiscal Outlook Has Deteriorated Rapidly

This is not to say that Fitch’s announcement will have no impact on markets. The immediate response has been characterized by a modest bear steepening in the Treasury yield curve, an increase in interest rate volatility, and a decline in risk asset prices. Most investors have known for many years that the U.S. fiscal position was unsustainable in the medium-term, due primarily to the ever-growing burden of entitlement spending in an age of demographic decline. The price response to Fitch’s decision suggests some investors were not aware just how rapidly the near-term fiscal outlook has deteriorated in the last year.

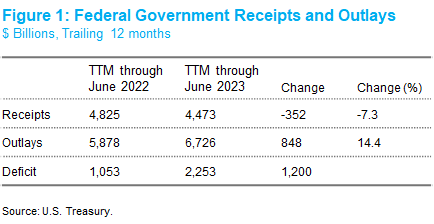

In the trailing twelve months through June 2022, Treasury accrued a $1.05 trillion deficit. By June 2023 that figure had more than doubled to $2.25 trillion. The larger deficit resulted from a 7% decline in receipts and a 14% increase in outlays.

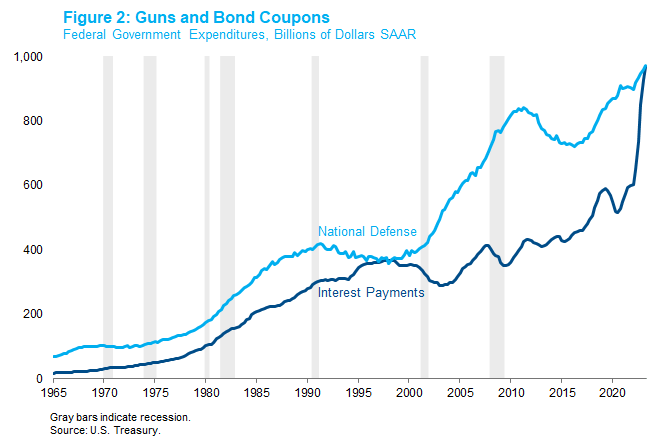

While legislation like the infrastructure bill and the CHIPS Act did marginally increase the deficit, these effects are small compared to more mundane items related to the broader economic environment. First and foremost is a 40% increase in interest expense as Treasury’s borrowing costs have spiked. This single line item accounts for nearly a third of the $848 billion increase in total outlays. The federal government spent the same amount of money on interest payments as on national defense in the second quarter (Figure 2). Treasury’s weighted average borrowing cost on all marketable securities outstanding is 2.79%, which is well below the prevailing level of Treasury yields today. Interest expense will therefore continue to rise as debt matures even if the yield curve stabilizes at current levels. Entitlement spending accounts for most of the rest of the increase in outlays, as medical cost inflation caused an increase in Medicare and Medicaid outlays, and a cost-of-living adjustment pushed Social Security payments higher. Inflation and higher interest rates have consequences for the federal government, just like the rest of us.

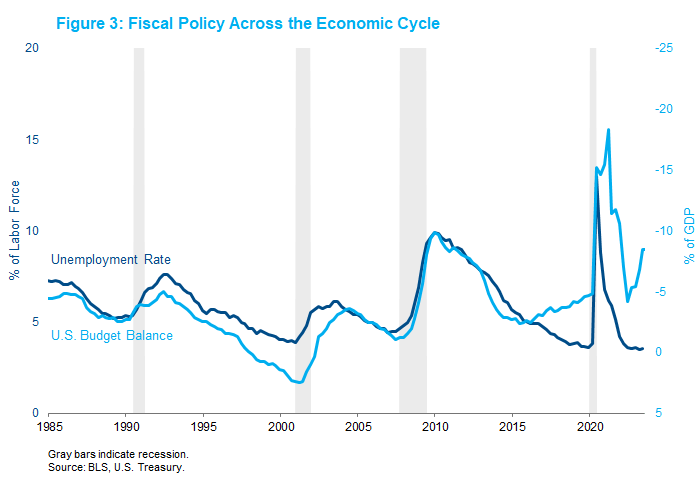

Tax receipts have declined as well between June 2022 and June 2023, not only from lower capital gains taxes as equity prices declined, but also from lower income tax receipts. This latter point is somewhat surprising given the strength of corporate and household incomes, and does not bode well for the near-term fiscal outlook given the state of the business cycle. In the later stages of an economic expansion, when the unemployment rate is low, the budget deficit is typically low and falling.

This is intuitive because strong household and corporate incomes typically lead to strong tax receipts, and a low unemployment rate generally leads to low outlays for automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance. When recessions arrive, the deficit usually spikes because tax receipts fall and automatic stabilizer outlays rise. Unfortunately, this cyclical pattern broke down starting around 2015, when deficits rose during an economic expansion. We therefore entered the pandemic with an elevated deficit and watched it soar to historic heights as the government marshaled an unprecedented fiscal response. Treasury’s borrowing costs remained low in large part because the Fed purchased more than 100% of net issuance in 2020.

As pandemic spending ebbed and the economic expansion accelerated, the deficit declined sharply and normalized somewhat relative to the state of the business cycle through the middle of 2022. The deteriorating fiscal position over the last twelve months has taken the deficit to 8.5% of GDP in the second quarter. If the economy enters a recession in 2024, the deficit will rise further from this elevated starting point. Unless the Fed has declared victory in the war on inflation, they may not feel comfortable implementing another quantitative easing (QE) program. In that case, the net supply of Treasuries that would need to be financed by the private sector would increase much more than it has in recent recessions. This could potentially translate to a significant increase in Treasury yields.

Cost inflation and a spike in interest expense have pulled forward the consequences of the U.S. government’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory. Fiscal authorities would be wise to reduce the deficit sooner rather than later to avoid testing the market’s ability to finance a recession-level deficit without the Fed’s support. While we still consider this to be a tail risk, the odds have increased somewhat as the fiscal outlook has worsened in recent quarters. A modest increase in the term premium today seems warranted in response.