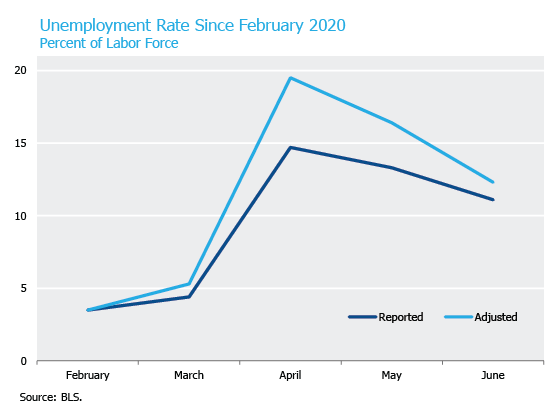

The labor market continued its spectacular recovery in June. The jobs report released on Friday reflected a net gain of 4.8 million jobs, almost double the increase from May. The monthly change in nonfarm payrolls has set a record in each of the last four months: two record decreases followed by two record increases. The unemployment rate fell to 11.1%, all the more impressive given the huge increase in labor force participation. As was the case in May, the underlying details of the report were stronger than the headline data suggest.

The June release supports our view that most of the labor market shock from the pandemic will prove temporary. In two months of economic contraction in March and April the number of workers on temporary layoff increased by 17.3 million. In the first two months of the recovery, 7.5 million of those had already been rehired. This is not a normal business cycle shock that permanently destroyed jobs; this is a public health crisis that required the temporary closure of whole swaths of the economy. While we expect that some of the remaining 10.5 million temporarily unemployed transition to permanent unemployment, the speed and the strength of the recovery thus far suggest the vast majority of them will get back to work quickly.

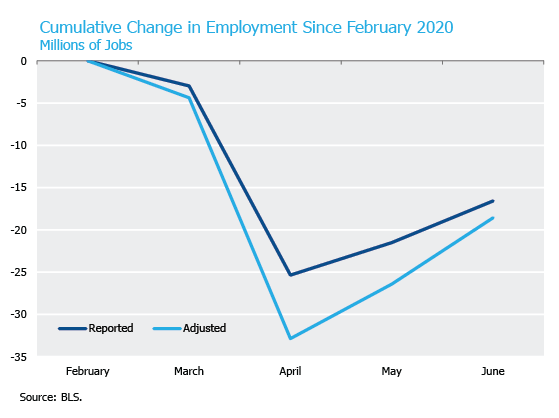

The labor market continues to experience an unprecedented degree of volatility as millions of workers transition between employment, unemployment, and departure from the labor force. Another 13 million workers were hired in June, offset by almost 8 million separations for a net employment gain approaching 5 million. In our view, the simplest way to cut through the noise and assess the magnitude of the damage is to monitor the total number of employed workers. This figure declined from 159 million in February to 133 million in April, a net loss of more than 25 million jobs. Employment increased in total by 9 million in May and June, effectively recovering about one third of the employment loss.

Those headline figures only tell part of the story. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) has been reporting since March what they believe to be a large misclassification error that understates the magnitude of the employment loss. Specifically, the BLS argues that millions of workers have been erroneously classified as “employed, but absent from work” when in fact they were furloughed and should have been classified as unemployed. If we adjust the official data to include these misclassified workers, the actual employment loss between February and April was 33 million workers and the adjusted unemployment rate peaked at 19.5% rather than the reported 14.7%. This suggests that job gains in May and June totaled 14 million or almost half of the true employment loss in the previous two months. The hole in the labor market was larger than reported, but it is being refilled more quickly.

Eye-popping figures like 33 million lost jobs or 40 million initial jobless claims have certainly shocked many observers including us. But the true damage to the economy was never as bad as those data points would suggest, and comparing them to historical experience was a misleading exercise. In the last three economic recoveries the unemployment rate declined by an average of 0.05% per month. At that pace, it would have taken 27 years to lower the unemployment rate from the adjusted peak of 19.5% back to the February level of 3.5%. Instead, we’ve already lopped 7.2% off the adjusted unemployment rate in just two months.

If the jobs recovery continued at the current pace, we would regain the adjusted February employment level in just two more months. That won’t happen. The next 14 million jobs will certainly be harder to regain than the first 14 million were. It’s possible that the elevated separations rate in May and June reflect permanent business closures rather than temporary shutdowns. The risk remains that the current case spike or a second wave of the virus could seriously reduce overall economic activity and job growth. The June data are good but they are in the rearview mirror. High frequency indicators of labor market activity suggest the pace of hiring has slowed in the last few weeks. If hiring momentum stalls, we may find a larger-than-expected overhang of permanently unemployed workers. This residual pool of labor supply might be drawn down at a pace closer to a typical recession.

Despite these concerns, the employment data through June remain consistent with an optimistic view on the nature of this most unusual economic cycle. This year’s labor market contraction was more sudden and severe than anything in American history, but it was never as bad as the headline data suggested. Our hope is that it continues to recover in a similarly atypical fashion.