Why Yield Spreads Across Currencies Need Translation

We have observed (with some bemusement) how the financial media often compares the yields on different countries’ debt without adjustment for the different currencies in which the debt is denominated. By overlooking a currency adjustment, investors may get a distorted risk-return picture when comparing sovereign bond yields.

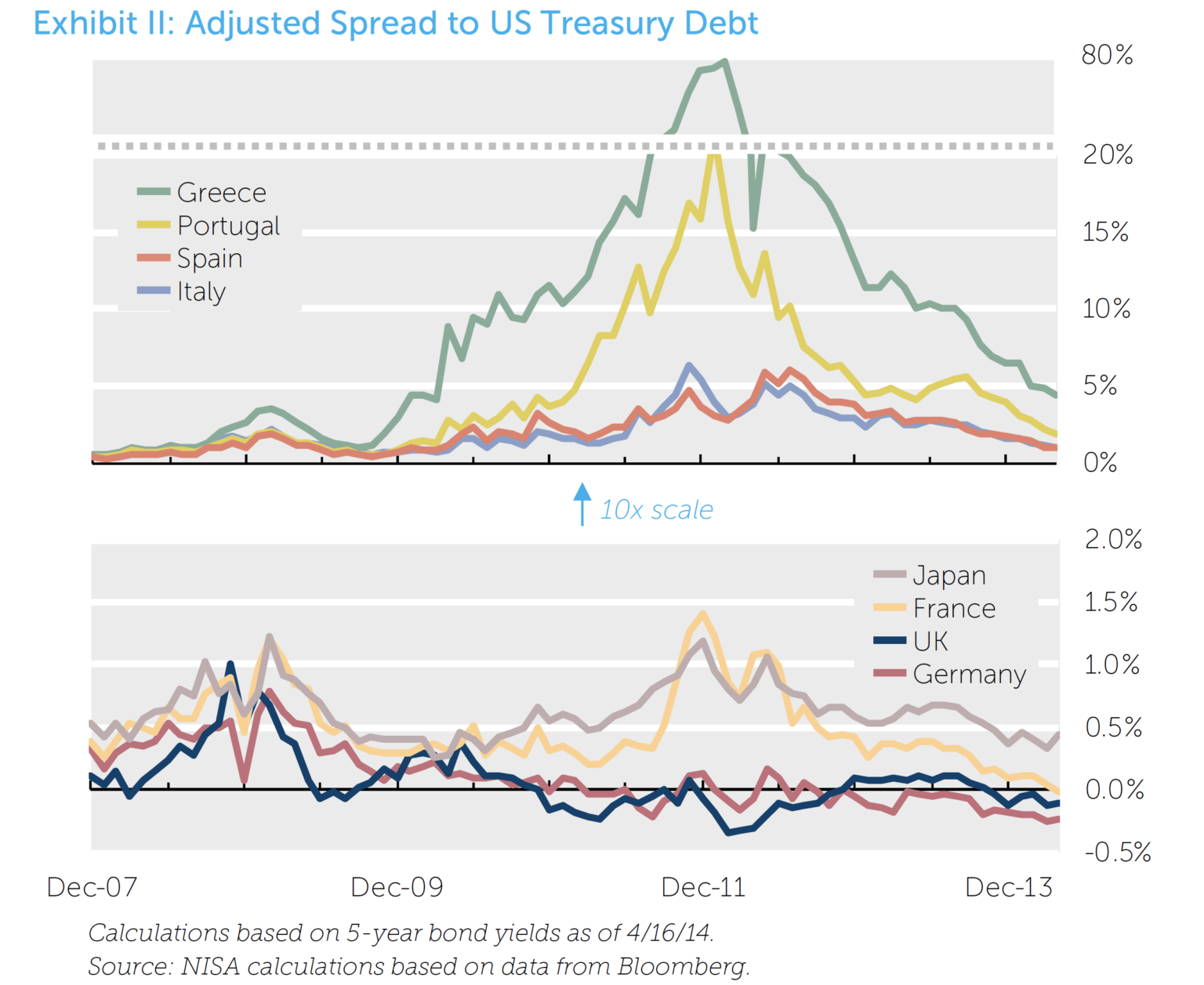

A lot of attention is paid to the interest rates at which a country can issue debt, and for good reasons. The “spread” or difference between a given country’s debt and a risk-free rate is directly related to that country’s default risk and, by extension, the overall health of its economy and political system. The stability of the Eurozone is often assessed this way, for example. The periphery countries like Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain play the role of canaries in the coal mine, with spikes in the spread of their debt seen as forecasts of trouble ahead for the entire region.

To glean any real information from a spread measure, we must first make sure the yields are apples-to-apples in currency terms. To see why, recall that nominal interest rates can be broken into three primary components. The first is a real rate that reflects compensation for delaying consumption. The second component is an expected inflation rate to maintain purchasing power, which can vary significantly from country to country. Lastly, a credit spread compensates the investor for any default risk.1

Nominal yields in different currencies often differ for the relatively uninteresting reason that inflation expectations are different (component #2). This makes it impossible to look at the nominal yield and discern anything about the credit spread (component #3). The fact that euro-denominated German debt is trading at yields below dollar-denominated US Treasury debt does not by itself indicate the US Treasury is a riskier credit than Germany. It could simply mean that inflation expectations for the euro are lower than for the dollar.

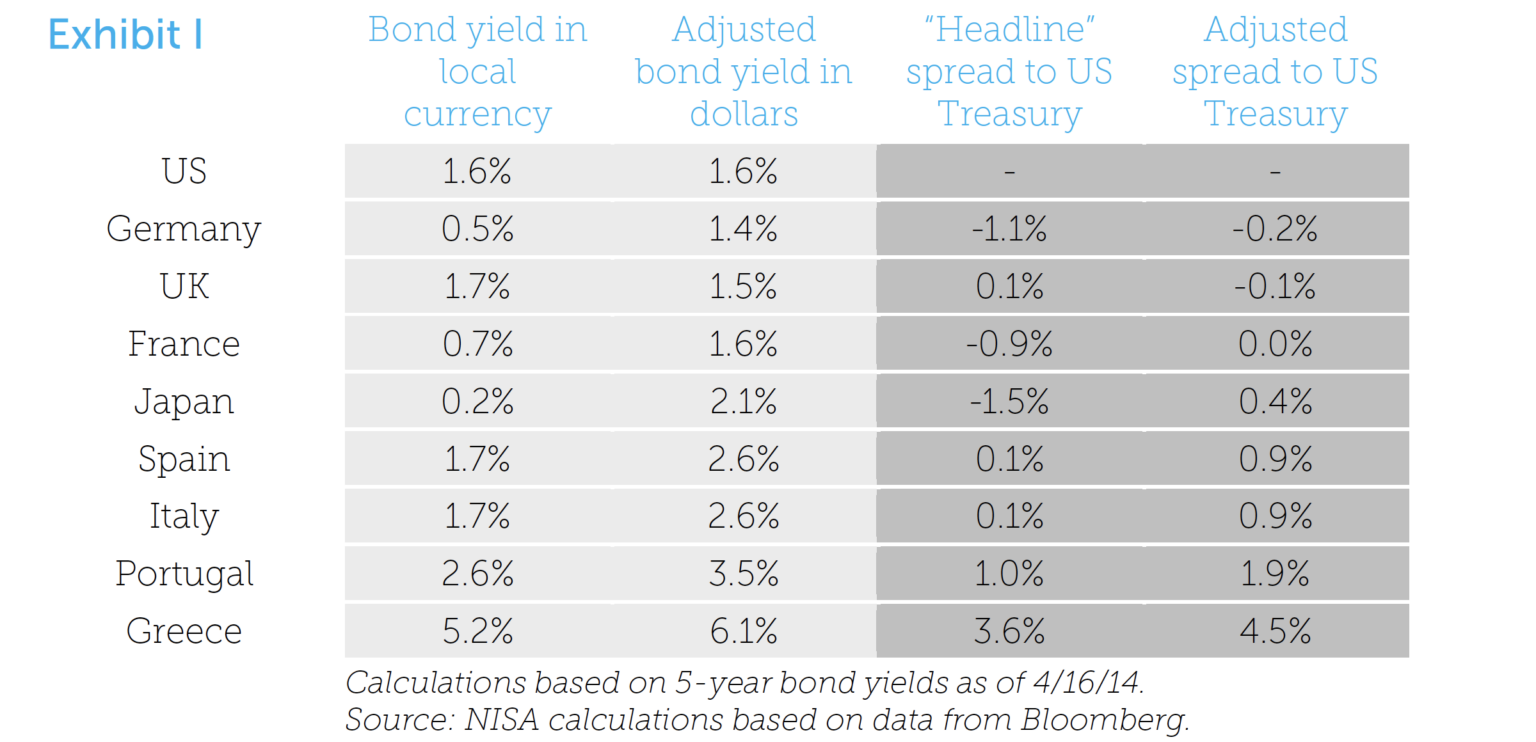

These inflation expectations are more than just abstract estimates. Since they are derived from active currency forward markets, they represent executable levels for a cross-currency investor. We can easily observe the market’s valuation of currency exchange by looking at currency forward contracts. For example, the current exchange rate is $1.38 dollars per euro, while a five year currency forward is trading at $1.46 per euro. That difference implies the market is pricing in about a 1% per year depreciation of the dollar vs. the euro, which is consistent with a 1% inflation differential. Only by calculating a US dollar yield for the German bond’s euro cash flows – effectively factoring out the currency difference – can we determine if German bonds are truly trading at a spread to US Treasuries that might indicate higher default risk. In Exhibit I, we show the results of this calculation for a handful of major sovereign issuers in different currencies.2

For example, we see that the “headline” spread of Spain’s debt to US Treasury debt is 0.1%, which is consistent with the highest grade, AAA-rated US corporate bonds. However, the currency adjusted spread of 0.9% is many times greater and presents a more informed measure of the relative risk of Spanish debt, implying a two notch rating difference consistent with A-rated US corporate bonds. In Exhibit II (next page), we show the historical adjusted spread over recent years.

Conclusion

The financial press tends to play fast and loose with the term “spread” when comparing sovereign bond yields, which can be misleading. To determine a meaningful spread between bonds, it is critical to measure the yield of each in a consistent manner. When bonds are issued in different currencies, one must translate the yields into a single currency before reaching any conclusions about how one issuer stacks up against another.

It would be foolish for a traveler to conclude that the weather is much colder in Madrid at 30 degrees (Celsius) than in Washington at 60 degrees (Fahrenheit). Investors face a similar pitfall in comparing bond yields across countries without adjusting for the difference in currencies – however, the consequences are likely greater than simply regretting you didn’t pack more sunscreen.