The IRS recently issued final regulations[1] that address modifying “lookback months” and “stability periods” for plan provisions such as interest rates used to calculate benefits. The lookback month specifies the reference period for the applicable interest rate and the stability period refers to the length of time between resets. For example, a plan may choose to use rate levels as of four months prior to the beginning of the plan year and reset the rate annually. The new regulations expand on previous rules that allow plans to modify either or both without violating anti-cutback rules as long as they provide the greater benefit (between the original and the modified provisions) for the next year.

While this hasn’t actually changed anything with respect to modifying 417(e) lump sum calculations, we see this regulatory update as a good opportunity to revisit this topic. Further, while not as dramatic as 2022, 2023 was another calendar year where plan sponsors may have noticed discrepancies between the accounting value of their liabilities and the lump sums they paid out.

As discussed in a prior perspectives piece,[2] 417(e) interest rates are used to determine the minimum lump sums plans may offer to participants in converting from traditional annuity benefits. The lower these rates, the higher lump sums must be. Ideally, for a plan that has hedged its liability’s economic exposure to interest rates, it wouldn’t matter where these rates are at any given time because the plan would be largely hedged against them. However, lookback and stability periods make it more complicated to hedge these lump sums since hedging assets will move with markets in real time while these lump sum payments will not.

While a plan could strive to be thoughtful about designing a hedge program with this in mind,[3] from an economic perspective, the optimal thing to do is to minimize both the stability period and the number of lookback months to the extent practical. Because amending a plan or updating administration can be complicated, there is likely a need for some lag given the amount of time it takes for 417(e) rates to be published. Nevertheless, for plans that have real economic exposure to this phenomenon there is a good argument for exploring this further.

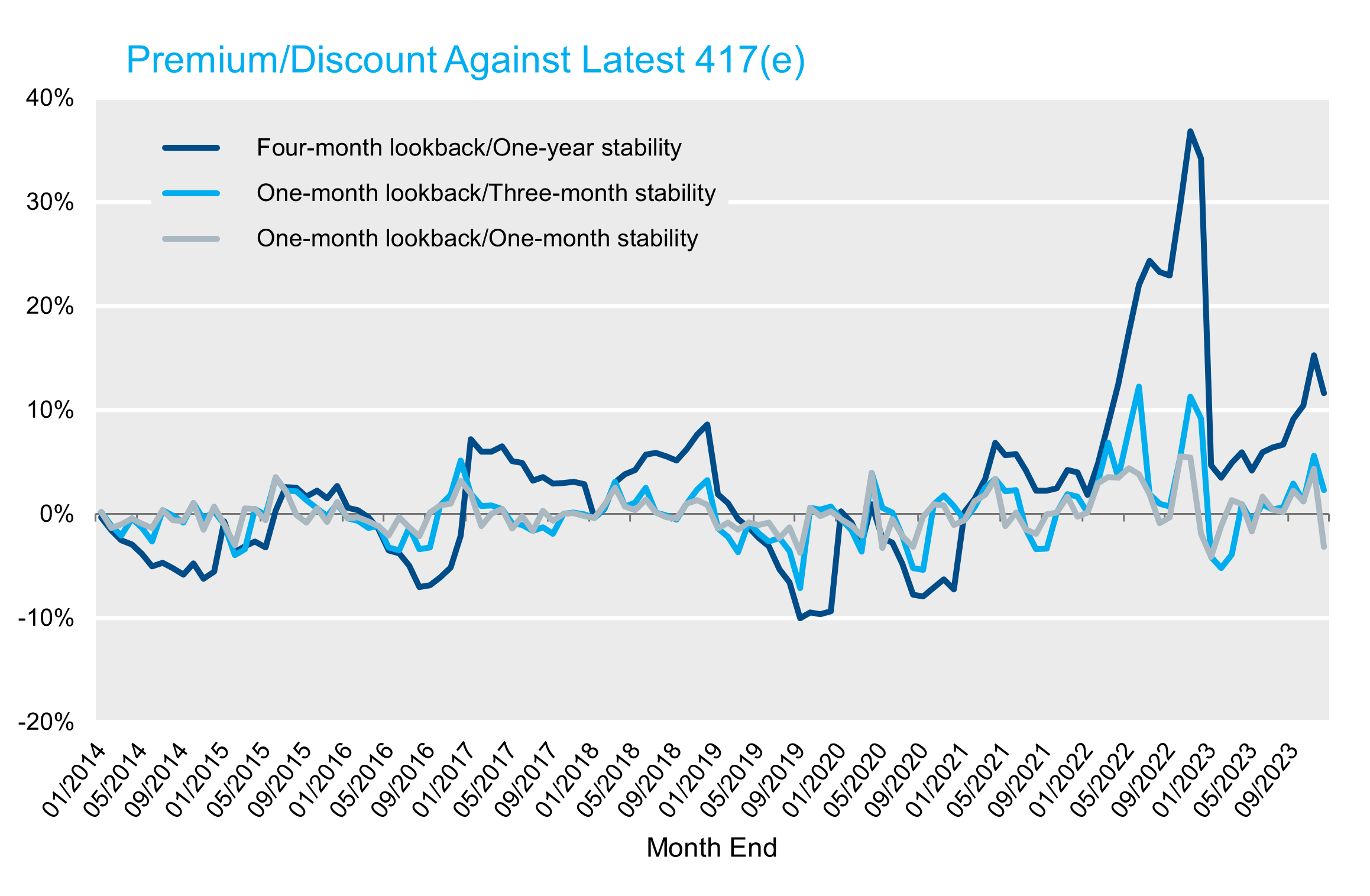

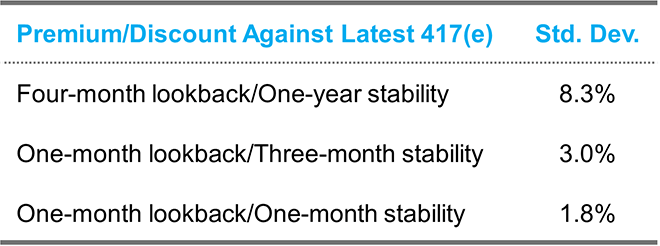

Below we illustrate the premium or discount a plan may pay to a 65-year-old participant electing a lump sum relative to a more mark-to-market value over the course of the last decade.[4]

Sources: NISA calculations, IRS.

We outline four key takeaways from this illustration with respect to implementing shorter stability periods and/or smaller lookbacks:

- Plan sponsors interested in valuing their liabilities in real time and understanding economic exposures to changes in rates (whether for specific hedging purposes or broader monitoring purposes) are expected to experience less volatility or valuation jumps when new applicable rates are recognized.

- Lump sums will be paid out at values more consistent with the economic value of the benefits promised as implied by 417(e) rates.

- There will be less potential for substantial gains or losses for actual lump sum payments versus what may be kept on the books.

- Finally, any option value plan participants retain in timing lump sum acceptances that is inherently but arguably not purposefully supplied to them[5] is reduced. Notably, this value is something that is typically not captured in valuations but would be expected to generate funded status bleed over time for plans where participants take advantage of this option.

We believe plans with longer lookbacks and/or stability periods should have conversations with their actuaries and advisors about making this change and we look forward to continuing these conversations.

[1] https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2024-00978

[2] Look Beyond the Obvious Impact of Rising Interest Rates

[3] There are indeed potential considerations, but they are often complicated and beyond the scope of this piece.

[4] We compare to the most recent 417(e) rates for each month, but note that 417(e) rates themselves are actually based on a one-month average of observed rates rather than being marked-to-market themselves. Similarly, 417(e) rates may not be entirely consistent with the discount curve elected by the plan to otherwise value liabilities. We don’t consider either of these to significantly alter the premise of this piece, but it is worth understanding that this may lead to modest differences between a calculated liability and an ultimate lump sum payment.

[5] While it is common to assume participants retire and accept lump sums at fairly predictable constant rates over time, the reality can easily be that participants time their retirements and lump sum acceptances when the rates used to calculate their lump sums are favorable, at a cost to the plan. As the illustration shows, for a plan with the four-month lookback and one-year stability period, there have been times where this discrepancy is on the order of a 40% premium to the sample participant.